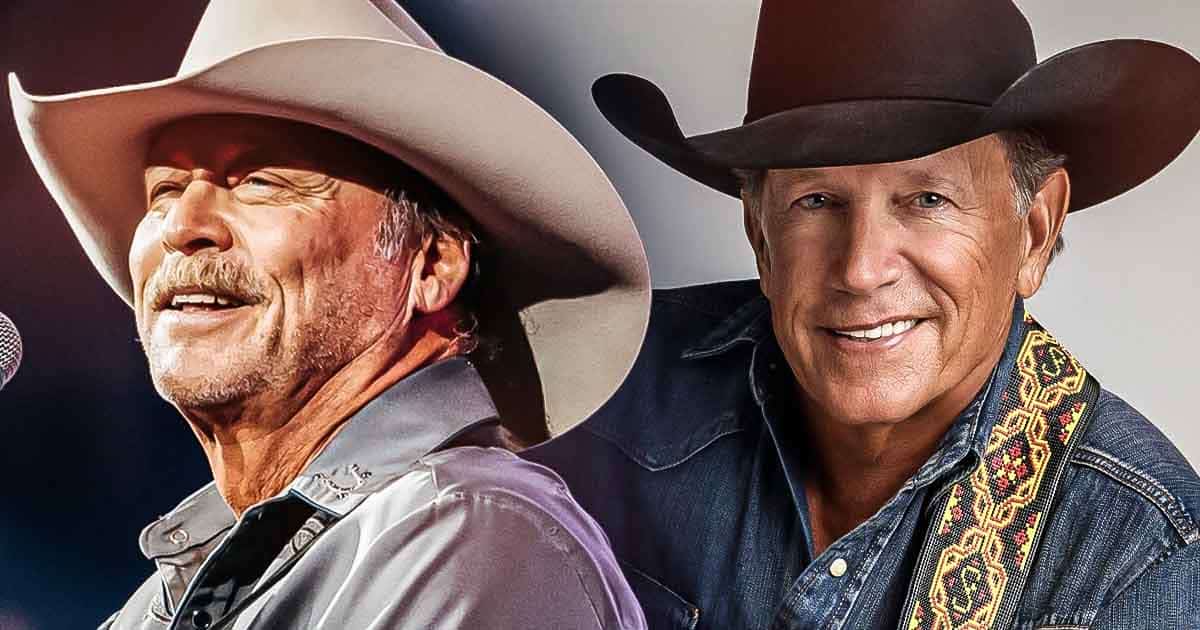

A simple cowboy song became a rites-of-passage anthem when two of country music’s most trusted voices took it on together, turning quiet sorrow into wide-open feeling and reminding listeners why some songs never fade.

The song, written in the early 1970s and cemented as a classic by George Strait in the early eighties, follows a rodeo cowboy who keeps going despite loss, injury and loneliness. When Alan Jackson joined Strait to sing “Amarillo By Morning,” the track was no longer just a singular statement of survival; it became a shared confession, a communal hymn for anyone who has kept faith with a dream long after the lights went down.

The duet’s power lies in contrast. Strait’s smooth, steady delivery carries the worn dignity of the cowboy; Jackson’s deeper, warmer tone answers like an old friend at the rail. Together they let the spare, fiddle-led arrangement breathe. The song’s short lines and clear images—loss of gear, the ache of travel, the stubborn decision to press on—are lifted by two voices that value restraint over flash.

Listeners who grew up with country on the radio say the duet brought new life to familiar words. Linda Harper, a longtime fan and retired cattle rancher, remembers sitting in her living room as the harmony took shape.

“It felt like someone had finally put a name to the weariness I carried,” Linda Harper, longtime fan, said. “Their voices made the story feel lived-in, not just sung.”

Music scholars point to the arrangement’s restraint as the secret. The production steers away from gloss and lets the old instruments—fiddle, steel guitar, simple piano—draw the map of the cowboy’s route. That choice keeps the spotlight on the lyric’s steady, almost stubborn hope.

“Strait and Jackson are traditionalists in the best sense: they deliver a song without showing off,” Dr. Michael Reyes, country-music historian, said. “This duet is a textbook example of two artists preserving an old form and making it speak to new ears.”

The song’s story is plain but rich: possessions lost, relationships frayed, the rodeo circuit’s constant motion. Those images connect to a wider audience beyond rodeo arenas. For many older listeners, the rodeo becomes a metaphor for any hard life lived on the move—farmers, truck drivers, teachers, veterans. The duet amplifies that universality by offering two distinct but complementary points of view.

Beyond the emotional pull, the duet is a technical lesson in harmony and taste. Both singers know how to leave space, to let a line hang long enough to be felt. Jackson’s baritone fills the song’s low corners; Strait’s even phrasing nudges the melody forward. The result is a recording that sounds familiar and newly urgent at once.

Fans and critics also note the cultural weight the pair brings. These are artists known for guarding country music’s older styles—honky-tonk phrasing, western swing touches, and a clear storytelling focus. Their pairing was interpreted by many as an act of stewardship: a deliberate reminder that classic country still has a place in living rooms and jukeboxes.

The duet version has since become a touchstone—played at small-town dances, on late-night radio shows aimed at listeners who remember when country was simpler, and in tribute sets by younger performers trying to learn the craft. It stands as proof that a restrained arrangement and two empathetic voices can turn a local story into a national memory—then stops as the chorus rises and the cowboy keeps riding.

Video