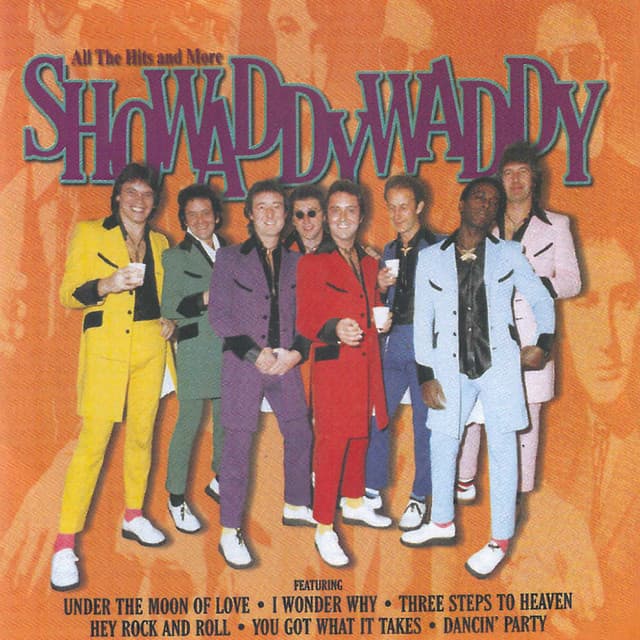

In the tumultuous summer of 1977, a year defined by the furious rise of punk rock, a storm of a different kind was brewing. As the Sex Pistols and The Clash tore through the UK charts, a group of eight men from Leicester, draped in spangled suits, launched a defiant act of rebellion. This was Showaddywaddy, and their weapon of choice was a sound so cheerful, so pure, it felt like a blast from a forgotten time. Their smash hit, “You Got What It Takes,” didn’t just climb the charts; it charged, peaking at an astonishing number 2, a feat that left many in the industry breathless.

For millions who lived through that era, the song is a powerful time machine. “The moment I hear that opening riff, I’m 17 again,” says retired mechanic John Peterson, 65. “The world felt angry, everything was changing, but that song… that song was pure joy. It was our escape.” But behind this joyous anthem lies a convoluted history, a tale of forgotten artists and disputed credits that has only recently come to light. The shocking truth is, the song was not a Showaddywaddy original. Its story begins nearly two decades earlier, with an obscure bluesman and a rising star of the nascent Motown scene.

The track was first popularized by American singer Marv Johnson in 1959, whose soulful R&B version became a significant hit. Yet, even that version is shrouded in controversy, with disputed songwriting credits involving the legendary Berry Gordy. “It’s a classic music industry story,” a source close to the band’s legacy claims. “A beautiful song passes through so many hands, its true origins almost lost to time, before being rediscovered and given a new life, a new heart, by a group of passionate revivalists.”

What makes Showaddywaddy’s version so enduring, what touches the very soul of their listeners, is its powerful, unpretentious message. The lyrics are a raw, honest declaration of love that flies in the face of materialism. “He doesn’t drive a big fast car / Don’t look a-like a movie star,” they sang, a message that felt almost painfully sincere in an age of growing excess. It was a celebration of character, a hymn to inner worth that rejected the superficiality of the world. For a generation caught between the anger of punk and the glamour of disco, Showaddywaddy’s music was more than just a good time; it was a lifeline. Their energetic, choreographed live shows were a spectacle, a vibrant party that recaptured a golden age. The song was a soundtrack for a generation longing for simplicity, a warm, fuzzy memory of a time when music felt a little less complicated and a whole lot more fun. Even now, hearing that boisterous opening can feel like a heartbreaking reminder of that pure, unadulterated joy on the dance floor.