The record opens like a summer storm. A whisper of electric piano. Rain on the horizon. But behind the mood lies a short, furious story of two men who found each other on a California beach and wrote a song that would haunt generations.

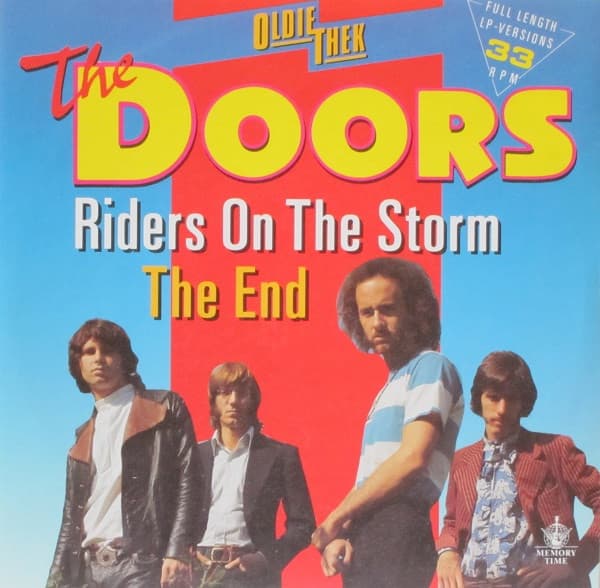

In the early 1970s The Doors were at the edge of something raw. The group had become a force of sound and mood. “Riders on the Storm” arrived as their most atmospheric work. It is a slow, jazz-tinged rock piece that feels like a film. It also marks the end of an era for the band and for Jim Morrison’s life.

Ray Manzarek, the band’s keyboardist, could still name the moment. He spoke in later interviews about a chemistry that was immediate and uncanny. He said their work balanced two sides of art — the orderly and the wild — and that balance sits at the heart of the track.

We just combined the Apollonian and the Dionysian. The Dionysian side is the blues, and the Apollonian side is classical music. The proper artist combines Apollonian rigor and correctness with Dionysian frenzy, passion and excitement. You blend those two together, and you have the complete, whole artist. — Ray Manzarek, keyboardist for The Doors

According to Manzarek, the song began as a loose jam. The band were experimenting with a country-leaning guitar rhythm. Morrison, known for sudden bursts of creativity, stood up and offered a line that fit the mood. From that moment the piece tightened into what listeners now know.

Morrison lept up and said, ‘I got lyrics for that!’ and he had… uh… ‘Riders on the Storm.’ — Ray Manzarek, keyboardist for The Doors

Those two lines of memory frame the song’s creation. Studio tapes from the sessions show a band moving carefully toward a darker sound. Manzarek’s Fender Rhodes gives the track its wet, shimmering feel. Robby Krieger’s guitar adds a twang that sits oddly with the storm drums. Morrison’s voice is low and fatalistic. Together they made a sound that felt like a warning.

The recording was made just before Morrison went to Paris with his partner Pamela Courson. He was trying to change his life, to get away from hard-living friends and a destructive scene. The mood of the song reflects a man on the move, torn between desire and doom. Listeners hear that tug in the line about being “thrown into this world” and in the repeated, almost ritualistic chorus.

Musically, the song is spare and precise. The band used space to create tension. Small details matter: the rumble of rain in the stereo, the soft whispered words near the end, the slow guitar fills that keep nudging the listener forward. For older fans, the track plays like a short, intense memory. It is both familiar and unsettling.

The song’s lyrics carry a threat and a tenderness. They mention a “killer on the road,” a warning that mixes violence and myth. At the same time, Morrison sings about love and protection. That double image — danger and devotion — is part of why the piece has endured. It mirrors the real life of the singer: a man who could be loving and reckless in the same breath.

The recording left a deep mark on rock history. It shaped how later artists approached mood and texture. For those who were there, it also marked a personal turning point. The band’s energy shifted after the sessions, and the sense of an ending moved closer as Morrison boarded a plane for Paris and the world watched as—