It arrived like a bright neon sign in a grey city and upended a career that many thought had already been written. “Downtown” was marketed as a carefree promise of nightlife and relief — and yet, behind its chiming piano and swinging beat, it carried a quiet loneliness that resonated across the globe.

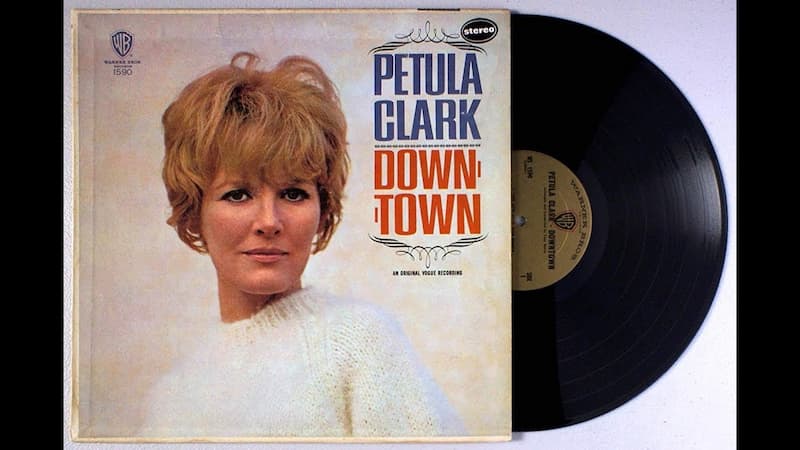

The song began life in the hands of English composer Tony Hatch and reached its full power when Petula Clark recorded it in a London studio late in 1964. What followed was a chain reaction: radio play, a transatlantic release, and an astonishing climb that made Clark one of the first British female singers of the rock era to top American charts. More than three million copies were sold in the U.S. alone, and the record shaped Clark’s image as a polished, international star.

The recording session itself has entered pop lore. Hatch brought a melody he had at first imagined for a doo-wop group. Clark, already famous in French-speaking Europe, heard the tune and urged him to finish it properly in English. In the studio the arrangement married orchestral pop with a mod shimmer: forty musicians, crisp strings, a rhythmic bounce and backing vocalists who made the chorus feel like a promise.

Engineer Ray Prickett, who ran the session, remembered how calm and professional Clark was in the booth.

She was a total professional and very easy to work with. — Ray Prickett, recording engineer

Tony Hatch later described the moment as a turning point in his own writing. What the pair produced was not a copy of a familiar hit but a new sound that fit the optimistic spirit of the era.

For the first time, I wasn’t copying Burt Bacharach. — Tony Hatch, composer and producer

Listeners heard more than bright lights and a good time. Clark herself has described the song as a kind of short film, carrying hints of loneliness amid its bustling chorus. The lyrics urge a person to escape the hush of home for the city’s loud, forgiving streets — where neon and music can briefly make troubles vanish. That double edge, a cheerful surface and a wistful interior, is a key reason older listeners still feel its tug.

The facts are simple but striking. The single was tracked in a London studio with top session players, including notable guitarists and a seasoned rhythm section. It earned a gold-selling record in the U.S., received major industry awards in the mid-1960s and later was honored by induction into the Grammy Hall of Fame. Clark also recorded the song in several European languages; each version found its own audience and proved the tune’s broad emotional reach.

Beyond sales and trophies, the song’s life carried on through covers and film appearances. From Frank Sinatra to Dolly Parton, artists reimagined it. Filmmakers used the track to underscore scenes of tension, escape and ironic cheer. Clark even revisited the piece decades later, recasting it as a slow, reflective ballad that emphasized what many had always sensed beneath the bouncing chorus: a plea to be seen.

For the generation that remembers the original, the track is a time machine. It carries the sound of an era when cities felt newly alive, when a chorus promised company and a bright window offered a way out. For Clark, Hatch and the musicians in that crowded studio, it became a rare combination of craft and fortune that turned a kitchen-moment melody into a global anthem. And yet, every time the first notes play, there is a small catch in the throat — the sense that the bright lights are waiting, but so is the lonely person who needs them, standing just inside the shadow of a doorway, wondering whether to step——