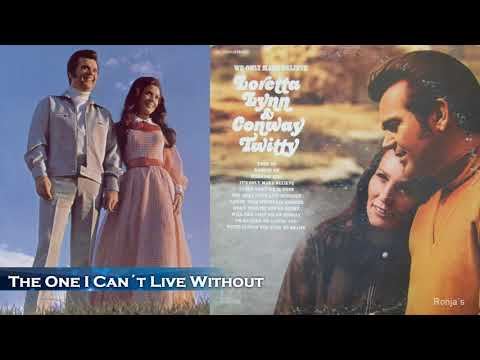

A gentle, aching duet can stop a room full of strangers and, in a moment, turn them into something closer to family. That is the quiet power of “The One I Can’t Live Without,” the Conway Twitty–Loretta Lynn pairing that has lingered in living rooms, church halls and jukeboxes for decades.

First heard in the early 1970s, the song is a plainspoken declaration of dependence and devotion. Its melody is simple, its language direct — and that is precisely why it still lands with an audience that grew up on radio and record players. Twitty’s warm baritone and Lynn’s clear, honest soprano fold into each other like two familiar hands clasping. The steel guitar and fiddle around them give the piece a homespun comfort that feels both nostalgic and immediate.

Listeners who remember buying the single or catching the performance on television talk about it as if they are revisiting a comforting old friend. The chemistry between the two singers is obvious; it is a duet that reads like a conversation rather than a showy display. In short bursts of lyric, it tells a story many people recognize: life is better, safer, and brighter when shared.

“When I hear that opening line, I’m back in my kitchen with the radio on, and everything feels right. They sang like people who had lived and loved — it wasn’t flashy, it was true.” — Elaine Carter, 72, lifelong country fan from Kentucky

Music historians and those who worked behind the scenes in Nashville point to craftsmanship. The arrangement is spare by modern standards, letting the words breathe. The instruments act as punctuation, not distraction. That restraint helped shape duets through the 1970s and set a template for countless pairings that followed.

“What Twitty and Lynn perfected was conversational intimacy. The production serves the singers, and the singers serve the sentiment. Younger artists still borrow that template without always naming the source.” — Dr. Robert Jenkins, country music historian, University of Tennessee

There are concrete reasons the song endured. Radio stations that catered to older listeners kept it in rotation long after other hits faded. Duets were a staple of the era — a format that highlighted relationship stories and allowed two distinct voices to tell one tale. For many fans, the track is less about chart positions and more about the ritual of listening: the record that played while making supper, the two voices that reminded them of their own marriages or lost loves.

Behind the recording, session players in Nashville added touches that gave the song its warm texture. A steel guitar slides like a memory; a fiddle line tugs gently beneath the chorus. Those elements, combined with plainspoken lyrics such as “you’re the one I can’t live without,” make the song easy to hum and hard to forget. Musicians who rode the Nashville circuit recall how a single night in a small hall could turn into a chorus of voices singing along.

The song’s impact is seen in small, persistent ways: cover versions by local bands, elderly couples requesting it at community dances, the way it resurfaces on tribute shows and radio hours aimed at listeners over 50. It is not a showpiece of complicated phrasing or dramatic theatrics; it is, instead, a steady presence that keeps surfacing in lives that prize memory and constancy.

That steadiness is also where the tension lies: a song so openly sentimental can be dismissed as simple, yet its simplicity is what pierces. Older listeners, in particular, hear more than a melody — they hear decades of ordinary life, punctuated by moments of tenderness and hardship, all carried on two voices that seem to know each other’s next breath. As the chorus rises again, the years fall away and the room grows very still—