In the turbulent summer of 1964, America was a nation on edge. Headlines screamed of Freedom Summer Project volunteers missing and murdered, US troops deployed to Vietnam, Malcolm X’s powerful call for “freedom by any means necessary,” and the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964 being signed into law. Against this backdrop of political and cultural upheaval, a Motown dance track exploded into the airwaves — “Dancing in the Street” by Martha and the Vandellas.

Penned by the legendary trio Marvin Gaye, William “Mickey” Stevenson, and Ivy Jo Hunter, this electrifying anthem was inspired by a simple everyday scene in Detroit — people cooling down under water flooding from opened fire hydrants. Marvin Gaye noticed Martha Reeves, a Motown secretary, and suggested to producer Stevenson to try this song with her. The recording session was an intense moment of creativity, completing the track in less than 10 minutes over just two takes, after fumbling the first attempt when the recorder wasn’t on.

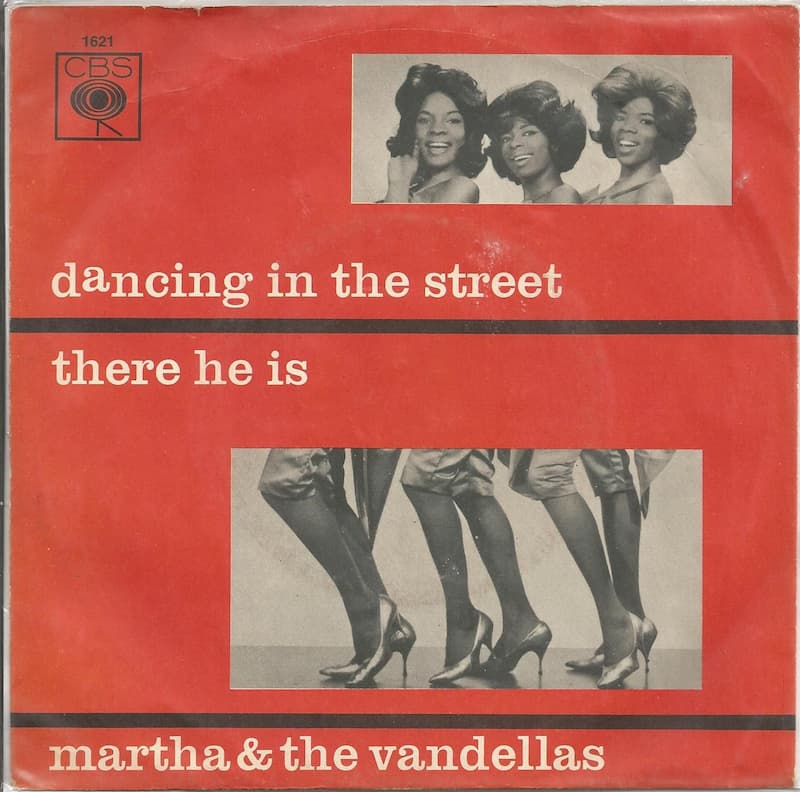

“Dancing in the Street” quickly became a signature hit for Motown, soaring to number two on the Billboard Hot 100 and clinching the number four spot in the UK charts. However, what transformed this catchy party song into something far more powerful was its adoption as a civil rights anthem during rallies and protests. The lyrics were interpreted as a nationwide call to riot and fight against systemic racism, oppression, and segregation, sending chills down listeners’ spines.

Martha Reeves passionately denied this militant reading when questioned by the British press, breaking down in tears, insisting, “It’s just a party song… I just want to be responsible for being a good singer.” But the controversy didn’t stop there; many radio stations pulled the track off the airwaves, fearing its incendiary potential.

In a fascinating turn, Mark Kurlansky’s 2013 book, “Ready for a Brand New Beat,” unpacks the song’s significance as the anthem for a changing America. Yet William Stevenson clarified the song’s ultimate message: “Kids have no colour. They would play out there as if they were brothers and sisters of every creed.” It was about integration, unity, and reclaiming space.

The very act of dancing in the street was a potent political statement — a peaceful, nonviolent declaration of power, joy, and visibility in public spaces often hostile to African Americans. The song’s message of defiant celebration and inclusive jubilation struck a nerve. Reeves later admitted the song symbolized the simple freedom “to dance in the street… where you don’t have to worry about policemen telling you you can’t.”

This anthem’s legacy is cemented in the Grammy Hall of Fame (1999) and immortalized in the Library of Congress National Recording Registry. Yet beyond its status as an unforgettable party tune, “Dancing in the Street” remains an explosive reminder of an era rife with conflict and hope, vibration and upheaval. It’s a story alive with the spirit of resistance set to an irresistible beat — a heart-stirring call that still beckons the world to the streets.

As the iconic lyrics declare:

“Callin’ out around the world

Are you ready for a brand new beat

Summer’s here and the time is right

For dancing in the street”

From Chicago, New Orleans, New York City, to Philadelphia, Baltimore, D.C., and the Motor City, the streets pulse with rhythm and unity — a stunning musical invitation to come together, dance, and defy the forces of division.

This remarkable hit, born from simple Detroit hydrant dances, captures a powerful moment in American history where music, politics, and culture intertwined explosively — sparking joy amid struggle, hope amid tragedy, and a timeless call that still resonates.