For generations, its haunting organ melody and sorrowful lyrics have echoed through time, but a cloud of mystery and tragedy has always shrouded the true story behind “The House of the Rising Sun.” For many mature listeners, it’s a staple of their youth, yet its origins are far darker and more debated than imagined. Was it a tale of a scandalous New Orleans brothel, or did it speak of the despair within a women’s prison? The truth is a gripping saga of fate, genius, and a single moment in a recording studio that changed music forever.

Digging into the song’s history uncovers two primary, and equally grim, theories. One points to an infamous location in New Orleans: a brothel allegedly run by a Madame Marianne LeSoleil Levant, whose French surname translates to “The Rising Sun.” It was said to be a place that led to the “ruin of many a poor boy.” A more chilling theory, however, suggests the ‘House’ was the Orleans Parish women’s prison, which featured artwork of a rising sun above its gate. An insider historian once remarked, “The lyric about a ‘ball and chain,’ found in many early versions, is a haunting clue that points not to fleeting pleasure, but to a life of hard time and regret.” The song, a traditional English ballad reimagined as an African-American folk song, was waiting for the right voices to carry its sorrowful weight to the world.

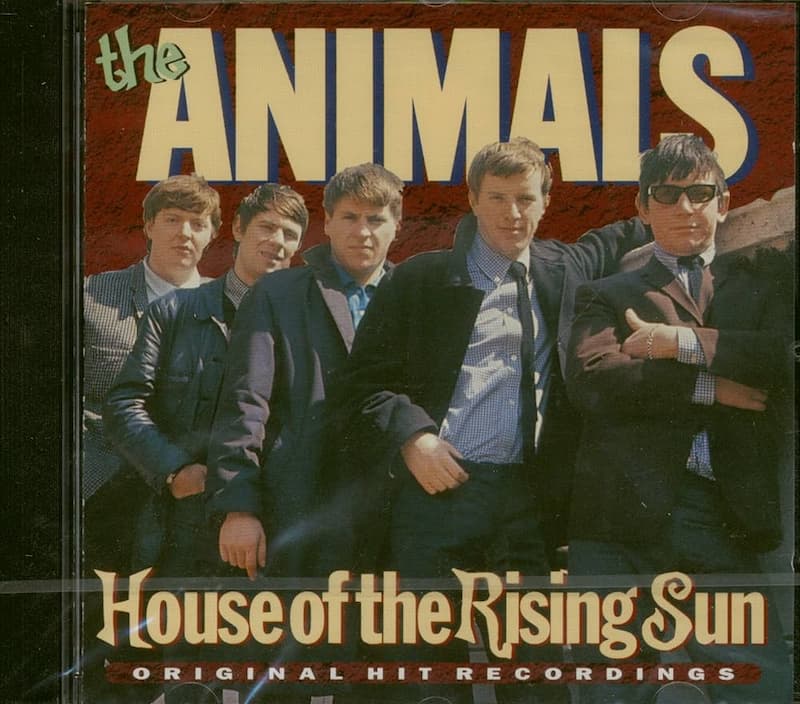

Those voices belonged to The Animals. The British band felt an almost spiritual connection to the tune. Lead singer Eric Burdon, in a moment of candid reflection, confessed, “‘House of the Rising Sun’ is a song that I was just fated to. It was made for me and I was made for it.” While touring with rock and roll pioneer Chuck Berry, the band used the song as their secret weapon. “It was a way of reaching the audience without copying Chuck Berry,” Burdon explained. “It was a great trick and it worked.” It wasn’t just a trick; it was destiny calling.

The recording itself is the stuff of legend, a lightning-in-a-bottle moment that occurred between tour stops in May 1964. Drummer John Steel remembers the session with crystal clarity. “We only did one take,” he recalled. “We listened to it and [producer] Mickie Most said, ‘That’s it, it’s a single.’” The band’s fiery perfection of the song on the road had paid off. But disaster nearly struck. The sound engineer declared the track was far too long for radio. In an era of strict time limits, he wanted to butcher it. But Most made a stand. As Steel recounted, “Mickie had the courage to say, ‘We’re in a microgroove world now, we will release it.’”

That courageous decision unleashed a global phenomenon. The song shot to #1, a raw, emotional masterpiece that resonated with hearts worldwide. In a stunning upset, it even knocked The Beatles off the top spot in the American charts. In a legendary act of sportsmanship, the world’s biggest band sent a telegram to their rivals. It read simply: “Congratulations from The Beatles (a group).”